Is there a correct way to use feminism to improve women’s lives? There seems to be no shortage of theories, role models, mentoring schemes or coaching programmes, all jostling for prominence. Some even claim to offer the definitive analysis of what’s wrong and to promise a total cure.

I have twenty years’ experience as a training consultant in communication, influencing and public speaking for clients of many hues and flavours. I pass on insights, skills and practices to enable them to persuade others, and to have choices about the impact they make. Much of what I teach has its origins in the other side of my double life – theatre-making. The approaches are to do with performance and creativity. Although the techniques themselves are genderless, the people deploying them are gendered, of course, as are their audiences. Their relationships are conducted within particular cultures with particular ways of doing things that often appear – to their natives, at least – immutable.

As a feminist myself, my values inform my own practice as a coach and tutor. There are many occasions, whether with single sex or mixed groups, that I have to admit that I have sneaked in a little bit of feminism under the radar when the stated purpose of the workshop was simply to equip people to be better public speakers. At other times, it’s been easy to be explicit about my agenda.

Coaching to develop voice and presence may be a pragmatic, individualistic response to the challenges thrown up by gender and culture. It has recently come in for some stick from a few Ivy League academics; Hermina Ibarra, Robin J. Ely, and Deborah M. Kolb take a dim view of me and my ilk in Women Rising: The Unseen Barriers in the Harvard Business Review, 1 September 2013.

Their piece investigates why women are still held back in their careers despite the good intentions of companies. They recount how many women are caught in a double-bind, damned if they do conform to stereotypes and damned if they don’t. The authors try to maintain a distinction between how women are perceived and their actual identities as people, speaking carefully about “conventionally feminine style”. Despite all this tightrope-walking, they don’t altogether manage to avoid generalisations themselves.

They critique the work of communication coaches by claiming that attempts to give women support in career advancement is based on “the premise is that women have not been socialized to compete successfully in the world of men, so they must be taught the skills and styles their male counterparts acquire as a matter of course.”

I don’t teach women to behave as men. Moreover, I disagree that the non-verbal expression of informal power (or ‘status’) – if this is what they mean by the vague phrase “skills and styles” – is an intrinsically male attribute. I also take a nuanced view on how status should be deployed when influencing others; dominance is not always best policy – for anyone.

My contention is that everyone benefits when there’s equality of contribution from the most diverse range of voices. My role is to empower my clients, whoever they are. When individuals are relaxed, they have choices about how to communicate. Rather than finding themselves driven by flight or flight mechanisms into behaving according to what they might consider culturally acceptable modes, they can pick what works in the moment. If anything, as communication coaches we are de-socialising people.

Ibarra, Ely and Kolb follow up this misconception with another claim for which they provide no evidence:

“Overinvestment in one’s image diminishes the emotional and motivational resources available for larger purposes. People who focus on how others perceive them are less clear about their goals, less open to learning from failure, and less capable of self-regulation.”

How does one quantify “overinvestment”? It seems that, for the authors, any focus on perception is suspect. Yet, perceptions do count. My clients and I manage to work together on clarifying purpose and crafting the message itself as well as influencing the audience’s perceptions of the speaker, not just through language but also non-verbal signals.

I’d like to relate some case studies from my professional life as a coach and trainer when I’ve worked explicitly with women in their aims to empower themselves. I’ll demonstrate that the coaching/training approach can accommodate discussion, practice, personal reflection and the test of the real world.

The corporate HR vice-president

“I remember when I started out in the late 1970s what things used to be like in the workplace for women. There was a senior guy who used to regularly toss a 50p coin across my desk and leer at me. ‘Go and get my fags, Blondie!’ he’d say. This was in spite of my having a post-graduate qualification in employment law.”

“Blondie” is now the HR Vice President of the EMEA division of a major multinational corporate. She is an energetic woman, with a warm sense of humour and a stylish taste for sharply-tailored, jewel-coloured dresses. Attitudes have shifted since the seventies, and cigarettes are a lot more expensive. Blondie is not the VP’s real name, of course.

The VP had identified that her mainly female team of HR managers were struggling with influencing upwards, and she wanted them to be equipped with non-verbal communication techniques to manage better. I’ve collaborated with her on several occasions, creating and delivering workshops for her team and coaching her directly in how to train others.

According to the VP, these workshops have had a positive impact, not least because they now have a common language to discuss body language and power. She reinforces the broad portfolio of soft skills training programmes by mentoring women in her team herself. One, she describes as “competent, but on the dull side!” She seems determined to light her mentee’s spark, and fan the flames of her ambitions.

Her approach is constructive rather than merely critical. For instance, she believes men have vulnerabilities as well as women, but that it needs to be acknowledged that the different genders handle their vulnerabilities differently.

“But it’s not all sorted,” she says. “And it’s still more difficult for a woman to make her voice heard than it is for her male colleagues. I’m the only woman in a senior team of alpha males. Most of them don’t have any sense of caution or self-restraint, and they’re not great at listening. I have had to say – on several occasions – will you just let me finish this sentence?” she sighs.

She believes that women in power can benefit everyone, not just the female workforce. She reminds me what happened when she influenced the (male) Sales Director to join in our workshops on body language and power. The games, she reckons, unlocked everyone’s imagination and playfulness – which led to us roping in bemused but willing hotel staff in the role-play. This did much to open people’s minds to possibilities and develop their confidence. The Sales Director too became a passionate advocate. He rolled the training out across the division, leading to improved performance across the board. This action contributed directly to his promotion in the organisation. Listening to and valuing women’s contribution, the VP believes, is self-evidently good for business.

The VP emphasises that although overt sexism is no longer normal, there is still much work to be done to make the office a place where women and men work together on genuinely equal terms.

This seems to be a commonplace in the non-profit sector as much as in the corporate, according to many senior women with whom I’ve collaborated. I’m struck by the number of female CEOs of charities who profess to struggle with managing their relationships with male trustees. Several have disclosed to me how much energy they have to expend in containing male egos, when they would have preferred to focus unhindered on leading their organisations.

“But yes, things have definitely improved,” the VP adds, with a smile. “Taking the chance, getting noticed, was harder work back then. Now it’s more normal that everyone is considered for promotion, male or female.”

A member of a Women’s Empowerment group at SOAS

Naturally, younger women are doing it for themselves as well. Millennials have reinvigorated feminism by using social media campaigns to call out wrongs, such Everyday Sexism. More broadly, they are looking at conditions for women and approaches to change with a fresh eye. Inclusivity is a watchword. I’m intrigued as to how far this extends to supporting each other offline in what is still, for me, the ‘real’ world.

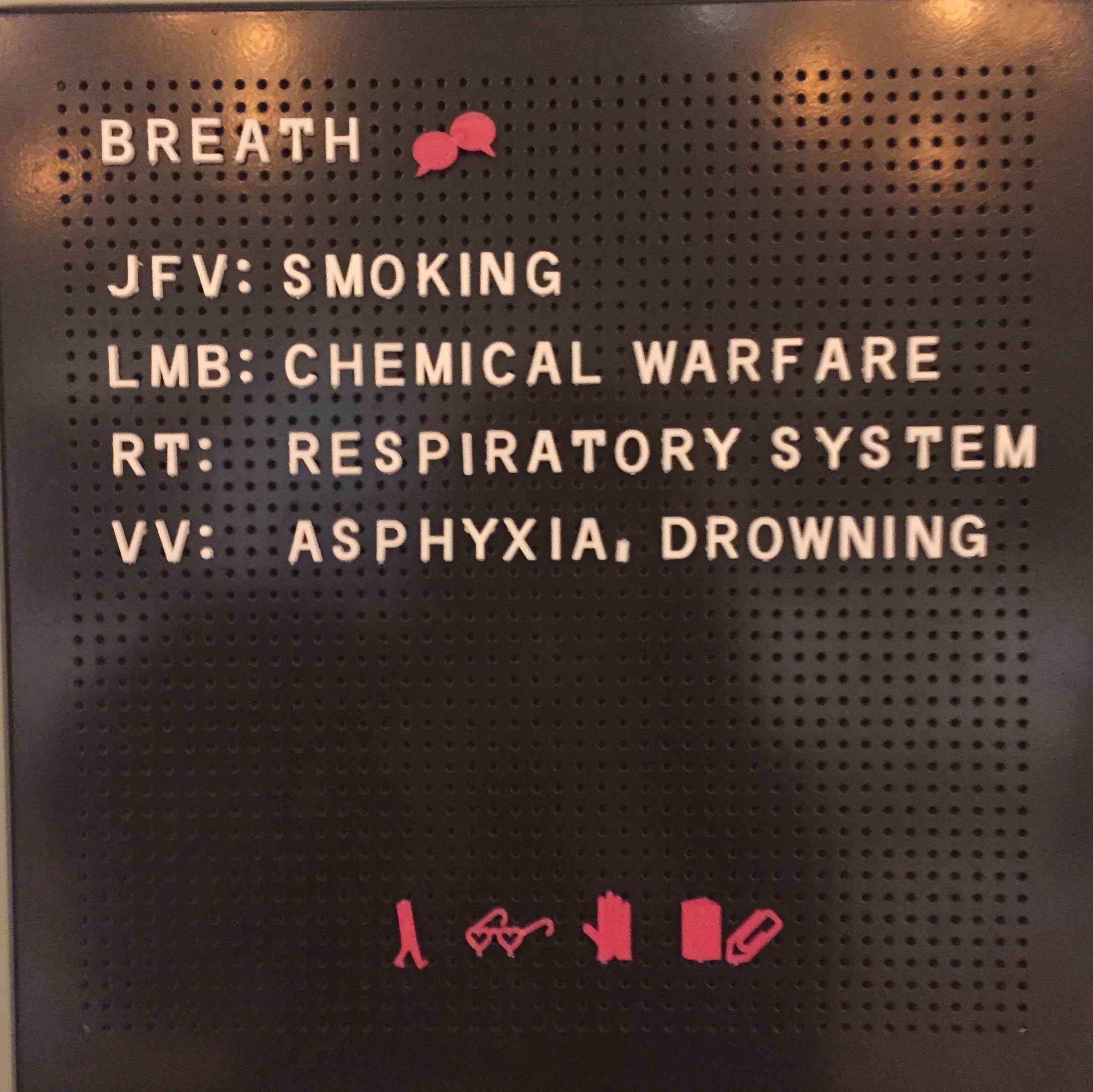

In Spring 2017, a few female MA students from the Centre for International Studies and Diplomacy at SOAS, University of London, took the initiative to set up a women’s empowerment group in response to what they felt was a male-dominated programme. They secured the support of the SOAS establishment along with a small budget to fund their project, which encompassed talks and panel discussions with high-level women (including the Director of SOAS, Baroness Valerie Amos); practical training workshops; and a Facebook group for sharing experiences and opinions.

I was involved in creating and delivering a workshop on women’s impact and presence. Along with the practical exercises and games, we discussed why “assertiveness” is so often touted as an ideal. Why should one always have to make sure one is coming across as nice while exercising power? And by the same token, why assume that it is always effective to project high status? From the feedback, it was evident that the women especially valued the physical nature of the workshop, and the chance to play.

Afterwards, I met with Carla Moll Pinto to talk further. Carla had been a lively participant in my workshop. She remarked that the role-play helped her discover that changing her body-language depending on the scenario was within her scope, and that it inspired her to see that she could “be anyone, with practice”. However, I was also interested in her wider experience of the Women’s Empowerment Group and its impact on her.

Carla is a part-time Masters student who is studying while continuing to work in a full-time job in advertising and marketing. Her professional goals are to work in corporate social responsibility and “to change things from the inside”. She didn’t initiate the group and doesn’t completely share the perception of some of her peers that the MA programme or the sector is male-dominated. She acknowledges that some women felt uninspired by the lack of diversity. Although there were brilliant female lecturers teaching on the MA programme, negotiation workshops were conducted exclusively by retired British diplomats, AKA “old white men”. She rejects the idea that this is problematic and puts it down to mere historical circumstance. “We can change the future,” she says, “And maybe in 15 years, we millennials will be the role models to future leaders.”

So what does feminism mean for Carla?

“I’m still in the process of understanding what I think,” she concedes.

One particular panel discussion, however, helped her move closer to crystallising her own views. The first two speakers extolled the benefits of working hard and being better than the boys. As chance would have it, both these speakers subsequently left the room after their contributions due to pressing engagements. Upon their departure, the third speaker tossed aside her notes aside in a dramatic gesture.

“Well,” said the lecturer, of her co-panellists, “What the hell was that? That was bullshit!”

A frisson of shock rippled through the room. The speaker was Noga Glucksam, an International Security lecturer at SOAS, and evidently a charismatic communicator. (“She was like an actress, actually,” Carla adds.) Immediately, Carla felt a sense of identification with this rebellious stance. What really resonated with Carla was the speaker’s opinion that we are all shaped by own individual past experiences, gender is merely one element in the mix, and that there is no specific way that women should behave.

Carla is a proactive, extrovert young woman with a dynamic attitude, yet she doesn’t consistently feel confident in every situation.

“I know things, but I don’t always know how to convey them, and I get nervous. I’m a good talker, but when it comes to technical things, sometimes I struggle. And it happens at home too, with my dad and my brothers. They always talk about politics and economics, and I feel I always lag behind. I’d rather be quiet than say something I’m not sure about.”

She attributes her challenges as much to other factors – having a disability, or speaking in English rather her native Spanish language – rather than exclusively to being a woman.

Since taking part in the Women’s Empowerment group, Carla has seen changes in close friends but also within the wider group. She recounts how in the Facebook group, that people “are more motivated to share things. Sometimes you see things and you don’t share them… because people label you. Always on Facebook, you need to be very careful about what you upload on your wall, because then it’s there, and then people can create an idea of you, or they label you – ah, this is a left-wing feminist, or a right-wing conservative. It’s really, really easy to judge somebody on Facebook and decide which side you are on. On the Empowerment Group page, people will share more there. Sometimes you will like what is uploaded, sometimes you won’t. But there is a space to share and I think that’s the main change that I’ve seen. In terms of life and relationships, I haven’t seen anything yet, but then it’s difficult, because we had exams and then everyone disappeared! It will be interesting to see what will happen this coming academic year.“

I’m struck by Carla’s caution about generalisations, and her sometimes conflicted feelings about taking a definitive position on the issues. She explains that she likes to base her opinions on evidence. The Group has given Carla an opportunity to research and become more informed. She says she has now moderated her individualistic, pragmatic stance, and now believes that there are some common issues that do need a collaborative approach for change.

I asked Carla what she thought should change for women specifically in the workplace. Her response this time was unequivocal: “Equal Pay, and in our sector, International Relations, there needs to be the involvement of more women.”

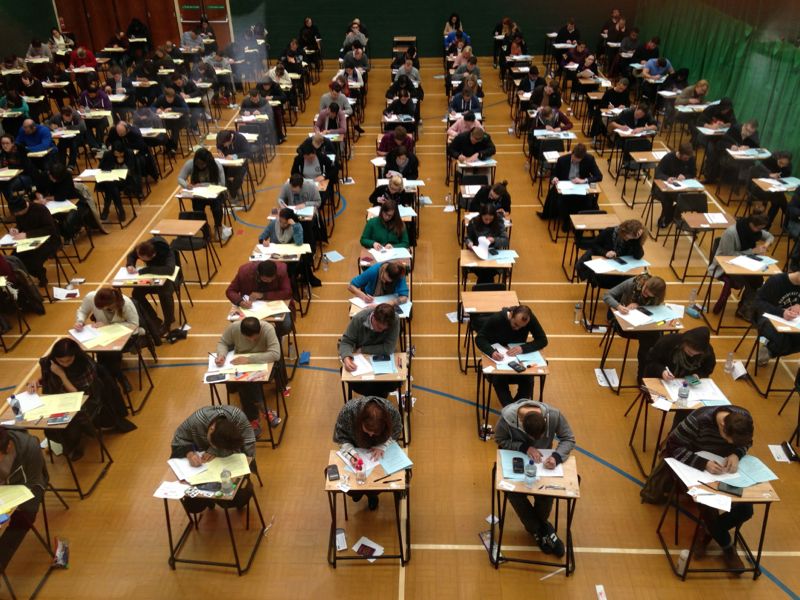

Young Girls in Newham

In 2014, I contributed to a project called the Emerging Scholars Intervention Programme (ESIP). Based in Newham, East London, this project identified girls who were promising, although not yet fulfilling their potential. The programme was provided for students in Years 8 through to 10 from three schools in the borough. It was delivered over ten sessions per year, and involved many different professionals from different fields of expertise. The programme’s aims were to:

- Develop resilience through challenge and support;

- Inspire new interest in subjects and topics through original perspectives and depth, increasing ability and achievement;

- Stimulate skills development for life, work and learning;

- Support development and expression of aspiration and a lifelong passion;

- Create a movement of change to inspire schools, parents and communities.

My first participation was as a delegate at the ESIP conference ‘Business Meets Emerging Scholars’, which was an opportunity for the students to meet professionals and business people. There were presentations from some of the girls and plenty of conversation. Taking part in our particular round table discussion, and particularly impressive, were an employment judge, Julia Jones; and Andréa Watts, a former art therapist and the founder of a company called UnglueYou, which helps people visualise their goals by using collage. Both women are black. Overall, the invited male and female professionals were a diverse group in terms of heritage, values and work life. So, the students had both the benefit of hearing different perspectives, and the opportunity to find points of identification with several different adults.

I contributed further to ESIP later in the year by providing a workshop for year 10 students called ‘Me and My Voice’. We explored how we send signals about who we are to others by playing improvisation and storytelling games, taking on different ‘status’ roles, voices and physicalities. Although this work involves exercises I normally use with adults, it was interesting for me to refashion them for a new age group and context. The girls grasped the objectives quickly, and responded to each other in a lively, creative way. This is not to say that they all necessarily found it easy, yet everyone took on the challenges with courage.

I had some of the most rewarding feedback of my career, and was impressed by the degree to which the students went away and thought deeply about how they could apply their discoveries to their lives. A comment from one girl was: “Fundamentally, I have learnt that I can make a choice and not let people dictate what my path is in life. Furthermore, that status is something we choose to present and we should make use of the choice.” Another student said: “I would love more sessions like this. The more uncomfortable the sessions make us feel, the more fears we conquer and the more confident we become.”

I met the girls again at the end of their programme when I was part of a panel evaluating their final presentations in which they each shared their own Big Audacious Goal. These were varied including: becoming a Member of Parliament; qualifying and embarking on a career as a pharmacist; and setting up an educational charity for young people in the developing world.

There were many more events, outings and mentoring sessions than I was involved in myself. All together, this was a resource-rich support for girls who would not have necessarily have allowed themselves the ambitions they grew into over the course of the programme.

This extraordinary project was the brain-child – surprisingly – of a man, Dr Simon Davey. If not exactly one of us, he is certainly a fellow traveller.

How to do feminism

While Women Rising: The Unseen Barriers provoked me with its misconceptions about own field of expertise, there were also other wider points the authors raise with which I want to engage. Reflecting on a few contrasting examples from my own collaborations with clients raises one big question for me: how can I pull together these diverse experiences and opinions to provide me – and perhaps others – with some guidelines on how to contribute towards redressing gender equality in the workplace in a way that feels both manageable and ambitious?

Purpose versus Perception

Identifying one’s purpose is vital for leading others in any endeavour and living meaningfully oneself. There is indeed a distinction to be made between purpose and perception. However, I’d like to explain in more detail why I think Ibarra et al set up a false conflict between “image” and “larger purpose”.

In my other life as an artist, I’m able to accomplish both the writing of a theatre piece and its subsequent performance in front of an audience. For me, these are complementary, not contradictory, activities. Once an idea is fully developed, it’s natural to want to put it out into the world and persuade others of its value. Establishing the credibility of the speaker is part of this task. In fact, if our early attempts at persuasion are not as successful as we would like, we need to go back to the drawing board to consider our larger purpose before we try again. This iterative process clarifies the message as well as its transmission. Sometimes we need to change the words, sometimes the delivery, and occasionally we need to rethink altogether. We call this rehearsal in the theatre. It is all about learning from failure and developing the necessary discipline to handle the stress of the difficult circumstances in which we must sometimes operate.

Telling women not to bother with how they are perceived is unhelpful. Anyone who wants to be persuasive should bother about how they are perceived. This means the opposite to enslaving oneself to others’ assumptions. Rather, it is about using one’s judgement about how as well as what to communicate.

None of the women I’ve trained report feeling constrained by rules or ‘masculinised’. Instead, they describe how they feel liberated to play a range of status behaviours, or how great it feels to use their voices with energy and freedom, or how empowered it is to be able to choose the impact they make on others.

Naturally, to begin with, all these techniques can do is give individual women leverage in an uneven playing field. However, the more women make conscious choices about their communication, the more others will respond to these women on their own terms rather than according to previous norms.

Respecting others’ experiences and viewpoints

We still have to contend with the long-held cultural assumption that masculinity and leadership are linked. It’s just as dangerous to generalise about femininity and female leadership styles, and to conclude that these are necessarily more benign. The women I’ve worked with have been extremely diverse – street-wise and naïve; self-effacing and show-offy; collaborative and individualistic; thick-skinned and sensitive to criticism; good listeners and bad. They have not all been held back by limiting assumptions about women and leadership, although undoubtedly some have been.

In the 1970s, “Blondie” had to be very determined to overcome the demeaning way she was treated early in her career. Knowing her story, I’m impressed that she has nevertheless become a top leader, challenging expectations of what it takes – that is to say, having the balls.

I don’t always share the same beliefs as my women clients. Sometimes I find their interpretations of their experiences at odds with how I would see things in their place. Women are not all the same with regard to what they attribute their challenges, or where they look for solutions. Different generations have different views about feminism.

For instance, in the same breath, MA student Carla Moll Pinto describes feeling less comfortable expressing her opinion than her brothers and denies that gender inequality is necessarily the main barrier to her confidence.

Ibarra, Ely and Kolb would ascribe Carla’s feelings to second-generation gender bias. They claim: “Most women are unaware of having personally been victims of gender discrimination and deny it even when it is objectively true and they see that women in general experience it”. I find this a troubling filter through which to look at women’s lives. How is it useful for women’s self-empowerment to insist on casting them as victims?

I do challenge clients on their views, but I would rather respect their version of their experiences than impose my own. It makes more sense to me to nudge women to experiment with different approaches to communication. They can evaluate for themselves afterwards if their perspective has changed along with the outcome of the interaction. Ultimately, we must accept Carla is the expert on her own complex reality.

Space to explore freely

A logistical/philosophical dilemma forced me to examine my own prejudices when I became involved with the Women’s Empowerment Group at SOAS. I was amazed to learn that the women planned to invite men to the workshops on Women’s Impact and Presence. I decided to engage with the Group on this matter with an open mind. There is much to be said for their commitment to inclusivity, even when this may look to older feminists like giving up hard won territory where we can be ourselves, without adjustments. I got as far as plotting how I could deploy the men in certain games to explore gender and power to challenge traditional roles. After discussing it, in the end, we agreed that it would be better to make this workshop women-only.

And yet, I have to admit to inconsistency on this point.

Those of us contributing to the ESIP programme at the Newham schools often remarked amongst ourselves that we should have been educating the boys alongside the girls, and teaching them to be feminists too. I wonder if, in a limited way, we could have helped forestall gender inequality before we needed a cure. Dr Simon Davey, however, counters: “I strongly believe girls take more risks when boys aren’t around. And boys are inherently less mature at the same age of adolescence.”

Age and timing may be factors in whether it’s productive to invite men into the process. And while men’s buy-in will ultimately be vital for real social change, involving them at every stage could compromise our journey.

Inner conflict, collective responsibility, individual action

How much should we work at changing the environment for all, and how much should we focus individually on surviving within the present one? Perhaps we don’t have to choose.

In my research for this piece, my client collaborators have been keen to recount anecdotes. In the telling, they have used our conversations to explore what meanings they could draw as they re-visited and re-appraised their lives.

It has struck me how much sharing stories has mattered to Carla and her cohort at SOAS, and how validating it has been for them individually and as group. “I can tell my experiences,” she says, “but I cannot tell you how to handle yours. You need to find your own way.”

What I’ve learned is that prescriptive approaches are not the way. Storytelling, experimenting with different styles, allowing space for inconsistency and uncertainty are the most honest and inclusive attempts we can make as feminists to make the world better for ourselves and others.

We shouldn’t only focus on purpose and perception, but also on possibility. If we’re searching beyond our present circumstances to alternate visions of reality, we should look to the arts. Read Margaret Attwood’s The Handmaid’s Tale or Naomi Alderman’s The Power to imagine yourself as a woman in another world – either horribly oppressed, or terrifyingly physically empowered. Watch Mad Men if you want to remember what office life was like before feminism. Listen to Beyoncé’s Lemonade to hear a feminism that can be wildly popular. Look at the photographic art of Nan Goldin for images of different ways of being a woman, or of Annie Leibovitz for the glitziest icons of female success. Then write your own story, sing your own song, or paint your own picture of the future.

This is why I import many exercises from the theatre and improvisation into my work as a coach. When I encourage playfulness in my workshops, the participants delight me with their originality. Given the tools and the permission to experiment, people are reinvigorated in their purpose. They discover a deeper emotional connection to their vision, and are inspired to be more inventive in how they structure their ideas, and therefore how they go on to communicate them. I see men and women collaborating on much more equal terms, as the novelty of the exercises disrupts established dynamics. Creativity is a greater leveller and a necessary ingredient if you are looking to change the status quo. The revolution will not be delivered on PowerPoint.

But enough gazing into the future. To borrow a trope from ESIP, my own Big Audacious Goal in this essay has been to boil down my insights to something simple I can act on right now, at least until a better idea comes along.

So, I have come up with this short checklist for my way of doing feminism:

- Collaborate, don’t impose.

- Explore, don’t prescribe.

- Imagine big, but be pragmatic along the way.